I am going to divulge a little secret, which isn’t really a secret, even though I have heard no mention of this date in the media, which is not to say that it has been ignored completely. I just haven’t heard anything said about it

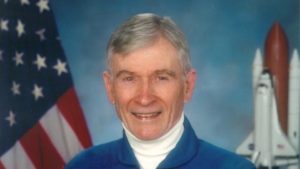

On this day 60 years ago, a young Marine Corps pilot took off aboard an Atlas rocket and became the first American to orbit Earth. John Glenn was a 40-year-old member of the first team of astronauts chosen by the space agency to lead this country into space. Alan Shepard and Virgil “Gus” Grissom flew the first two sub-orbital flights. This one was different. It fell to Glenn to become the first American to take three 90-minute spins around the globe and, thus, become part of American lore.

My mother and I were addicted to the space program in those days. I was not quite 13 years old. We had awakened several previous mornings waiting for Glenn to blast off aboard Friendship 7, the tiny Mercury space capsule into which he squeezed his body.

Mission Control gave him the go-ahead — finally! — on Feb. 20, 1962. Off he flew. Three orbits. That’s all, man. Then he came home and rode into instant fame and glory. The young pilot from Ohio, who flew combat missions during the Korean War, was hailed as a hero with ticker-tape parades and audiences with the president and royalty around a planet he had seen from a couple hundred miles in space.

Ah, but his public service didn’t end there. He resigned from NASA. Glenn entered politics and became a U.S. senator from Ohio. Glenn ran for president in1984, but unlike his Friendship 7 ship, his effort never left the ground.

Then came another thrill for Sen. Glenn and for those of us who followed the space program. NASA had gone through the Mercury, Gemini, Skylab and Apollo space programs. It had a fleet of space shuttles, those reusable ships that flew into orbit many times. One of them was named Discovery. In 1998, Sen. Glenn got the call to suit up once more. He trained along with his shuttle crewmates for a lengthy mission. NASA wanted to test the effects of zero gravity on old folks; Glenn qualified, as he was 77 years of age, making him the oldest individual to fly into space.

Ahh, but the Discovery launch a moment I never will forget. The controllers counted down the time, the booster rockets ignited, and the ship lifted off the Florida launch pad. The public address announcer told the world that Discovery had launched, carrying “six astronaut heroes and one American legend.”

And so … I recall the day 60 years ago that a young man — and please pardon the reference — with the right stuff flew into the sky and carved into stone his prominent place in our nation’s glorious history.