By JOHN KANELIS / johnkanelis_92@hotmail.com

Someone once said that to be called “Heavyweight Champion of the World” was tantamount to being labeled the “baddest dude on Earth.”

Everyone used to know the name of the heavyweight champion. These days? I cannot tell you unless I look it up in my World Almanac and Book of Facts.

I mention this because some of the sports networks this weekend have commemorated the 50th year since the Fight of the Century.

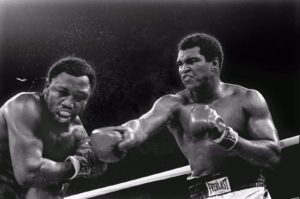

Yep, on March 8, 1971 two men fought for the heavyweight title. One guy was the champion, Joe Frazier. The challenger? A fellow named Muhammad Ali.

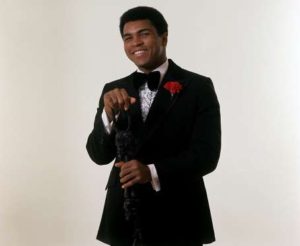

I’ll set the table briefly. I was a huge Muhammad Ali fan. I considered him “the champ,” since he was stripped of his title in 1967 because he refused induction into the Army during the Vietnam War. Boxing authorities stripped him of his license to fight. He became an iconic figure. He would win reinstatement and then the Supreme Court would rule unanimously that he should be allowed to fight again.

Ali returned to the gym and whipped his body into shape. He fought twice against quality contenders before squaring off against Joe Frazier.

The fight lived up to the hype. It was a brutal affair. Frazier won by decision. He floored Ali in the final round. They both were great champions. Although, I surely must acknowledge that Muhammad Ali was The Greatest.

Both men are gone now. Frazier died in 2011 of cancer; Ali died in 2016 of Parkinson’s disease. The fight game isn’t the same without them.

The Fight of the Century turned out to be all that it was trumpeted to be. There likely will never be a man-to-man competition that ever will measure up to what we witnessed a half-century ago.