I guess you could say that time is no one’s friend.

It takes its toll on human skill. Of course, eventually it catches up to all of us for the final time.

These thoughts came to mind as I’ve been watching and listening to the tributes pour in to the late Muhammad Ali — yes, it’s strange to attach that word right before The Champ’s name.

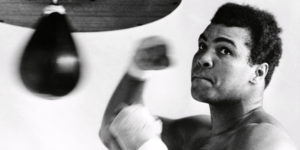

Ali came to the world’s attention as young Cassius Clay, a boxer with tremendous hand and foot speed in the ring. He didn’t block punches with his elbows or gloves.

He dodged them with his head.

He’d pull his back while the big left hooks or straight rights would whistle by. Clay would dance out of the way, peppering his foe with lightning-quick jabs and multi-punch combinations.

Then he would pull away again.

Well, time does not allow the human body to perform like that forever.

After he changed his name to Muhammad Ali, the boxer lost more than three years of his prime athletic life. The U.S. government accused him of draft evasion, the boxing authorities denied him his right to box and he spent most of 1967 and all of 1968 and 1969 on the lecture circuit, speaking out against the Vietnam War and against racism.

Then he came back.

But he was a different kind of athlete.

Time had robbed him of a bit of that skill he demonstrated with his quick reflexes. He no longer was able to dodge and dance away with quite the flair and panache he demonstrated as a younger boxer.

No, the boxer then became a fighter.

Sure, he proved to be unafraid to fight against injustice in the world.

However, when he was able to lace the gloves back onto his powerful fists, he became a fighter. He showed the world that his quick feet and hands didn’t signify an unwillingness to fight. That speed merely was a demonstration of the rare skill he exhibited in a most-brutal sport.

He was able to lend an extra level of sweetness to the Sweet Science.

As time marched on, though, Ali was forced the absorb more punishment from foes who a decade earlier would have flailed in futility.

He demonstrated another skill that many boxing experts admitted at the time they never anticipated. The Champ demonstrated that he had a fighter’s heart.

He became a warrior in the ring.

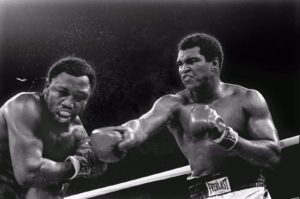

The Thrilla in Manila — his third epic fight with rival Joe Frazier, provided perhaps the most graphic example of his fighter’s heart.

In 1975, Ali was the champion. He started out quickly, trying to take Frazier out. Frazier survived that early-round blitz. He came back in the middle rounds, punishing his adversary with body blows.

Ali then summoned something from deep within him to rally in the later rounds. By the time the bell rang to end the 14th round, Frazier’s face was a bloody, swollen mess. Muhammad Ali the warrior had shown he had the heart of a champion — of a fighter.

Frazier’s trainer, Eddie Futch, stopped the fight — a drama in three acts — and made a decision I am certain to this day well might have saved his fighter’s life.

Smokin’ Joe said it best after the fight. “Man,” he said, “I hit him with punches that would have brought down the walls of a city. Lawdy, he’s a great champion.”

So he was. The boxer had become a fighter and revealed that time at least can be stalled a little while longer.