I remain utterly transfixed by the Ken Burns-Lynn Novick documentary series “The Vietnam War.”

It contains some of the most compelling television I’ve ever witnessed and I am so proud of PBS for its longstanding commitment to this type of educational broadcasting.

Having tossed out that bouquet, I want to offer this barb at what I witnessed tonight.

The series tonight focused on the Tet Offensive, which the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese launched against dozens of South Vietnamese cities on Jan. 31, 1968. “The Vietnam War” rightly points out that Tet likely was the political turning point, the singular event that turned American public opinion solidly against that bloody conflict.

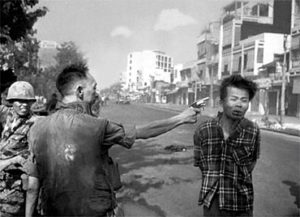

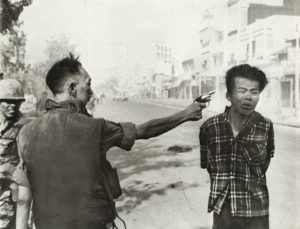

Tet also produced what arguably was the most singularly graphic moment in that war. It was the photo of Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan’s summary execution of a Viet Cong suspect.

Loan was head of South Vietnam’s police department when he found the suspect and shot him dead on a Saigon street. The picture would earn a Pulitzer Prize for Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams. It also would deliver a lifetime of misery for Gen. Loan, who was vilified because reporting of the incident at the time failed to the tell the whole story.

I wish the Burns-Novick documentary would have told us tonight about the media’s role in demonizing Loan.

You see, Loan shot the man dead because the suspect had been part of a VC hit squad that killed a colleague of the general — and his wife and six children. Loan knew about what had happened to his friend and his family. His men arrested the suspect. Loan ordered one of his officers to shoot the suspect; the officer balked.

So, Loan took out his pistol and shot the man in the head.

Nguyen Ngoc Loan had snapped. He proved to be a human being subject to human emotion,

“The Vietnam War” didn’t tell the whole story tonight, nor did it explain why — because of the lack of full reporting in the moment — that picture came to symbolize the absolute horror of war.

However, by golly, I am going to watch the rest of this utterly spell-binding television event.

I am hooked.