One of the traits one often hears about World War II veterans is that they don’t talk much about their combat experience.

They answered the call after Pearl Harbor; they shipped out to the Pacific Theater or to Europe and went about joining other Allied forces in defeating the forces of tyranny.

They came home after that great conflict, shed their uniforms and cobbled their lives together. They moved on.

The Korean War came a few years later. That one didn’t end with an all-out victory and unconditional surrender of our enemy. Indeed, Korea is still in a “state of war”; they only signed a cease-fire. Korean War veterans became part of what’s been called “the forgotten war.” They aren’t known either to talk much about their years in hell.

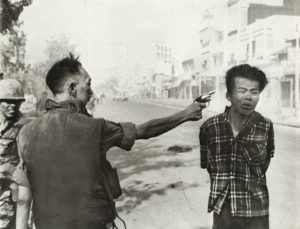

Then came Vietnam. The Vietnam War ended in a stinging political “defeat” for the United States. It still hurts. Those who feel the pain the most likely are those who served there. Roughly 3 million Americans suited up for that war. I was among them. I’ll get back to that in a moment.

Vietnam veterans are more likely to talk about their experiences than those who remain from World War II or Korea. It must be a generational thing. It also must be a bit of a hangover of sorts from the crappy treatment many of those young Americans got when they returned home.

Thankfully, that treatment is receding farther into our national memory. Americans woke up to the reality that the young men who participated in that war did so solely out of duty. They were ordered to go. They went. They did their job. They came back.

Perhaps their willingness to talk about it is a function of their search for affirmation that they weren’t the villains that many of their countrymen and women perceived them to be in real time as they were coming home.

I have no particular need to discuss my service during the Vietnam War. My contribution to that effort was so insignificant, I don’t have the need that many Vietnam vets have — even as we all have advanced into “senior citizenhood.”

In one week, PBS is going to premiere the broadcast of a truly landmark television event. “The Vietnam War” will run over 10 days, covering 18 hours of what I am certain will be a riveting documentary on the nation’s most divisive and emotionally crippling conflict.

One of the outcomes of this documentary, assembled by the great documentary filmmaker Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, should be to spark more national conversation about Vietnam, the war, its aftermath and how we have made the journey from back then to the present day.

***

The first five episodes will air nightly on Panhandle PBS from Sunday, Sept. 17, through Thursday, Sept. 21, and the final five episodes will air nightly from Sunday, Sept. 24, through Thursday, Sept. 28. Each episode will premiere at 7 p.m. with a repeat broadcast immediately following the premiere.