I’ve long had a terrible conflict of emotions as it regards the filibuster, a tactic employed in the U.S. Senate designed to stall the progress of legislation … and appointments.

The Senate this week did away with its 60-vote rule to end filibusters. The rule change allowed the confirmation of Judge Neil Gorsuch to the U.S. Supreme Court.

But it’s the filibuster itself that gives me pause.

My own political bias clouds my view of what the Senate did as it regarded Gorsuch’s nomination. Given that the Republican-controlled Senate blocked an earlier high court nomination because a Democratic president had put a name forward to succeed the late Antonin Scalia, I saw some justification in what Senate Democrats sought to do with Gorsuch’s nomination.

But is the filibuster really an essential element of governance? I’ve long questioned it. A filibuster occurs when senators object to an issue before the body. They can filibuster in a number of ways, but the classic method is to hold the floor for hours, days, weeks — however long it takes — to talk about anything under the sun.

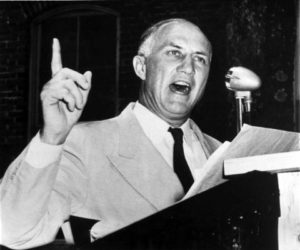

The Senate has had some champion filibusterers. I think of the late Wayne Morse from my home state of Oregon and the late Strom Thurmond of South Carolina. Those fellows could bluster seemingly forever on anything in order to talk a bill to death.

We operate our government on the principle of “majority rule.” The word “majority” doesn’t imply “super majority,” which is what the former Senate filibuster rule required. Majority means one vote greater than half. The Senate comprises 100 members; therefore, 51 votes constitute a majority. Shouldn’t that be enough to settle a policy argument on the floor of the Senate?

We elect presidents with a simple majority of the Electoral College. All it takes is 270 electoral votes, out of 538 total, to elect a president. Is there a more important electoral decision to be made than that? We don’t require in the U.S. Constitution a super-majority of electoral votes to choose a president. So, why do senators insist on filibustering and then require 60 votes to end it.

The filibuster seems to be an obstructionist’s tool. As one who believes in “good government,” this activity appears to me to work against that principle.